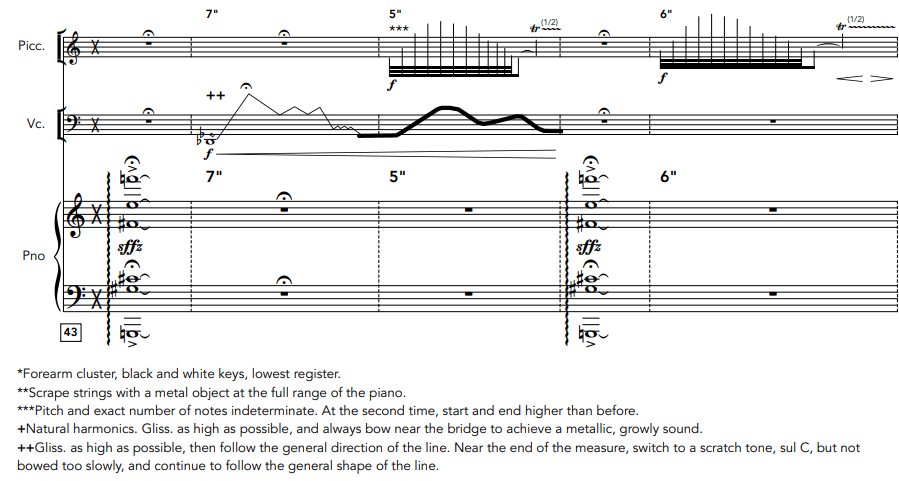

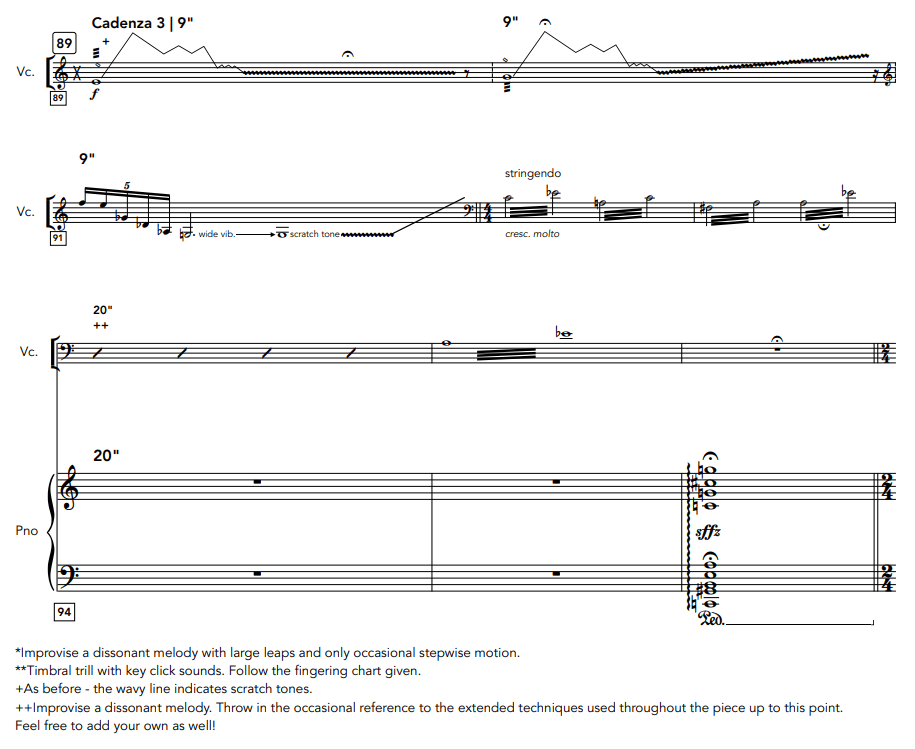

My new orchestra work Triple Threat has a solo section in the middle. Why? I believe it is important for young musicians to begin composing and improvising early on. Click here to sign up for more info about how you can be a part of bringing this piece to life!

Solo Section

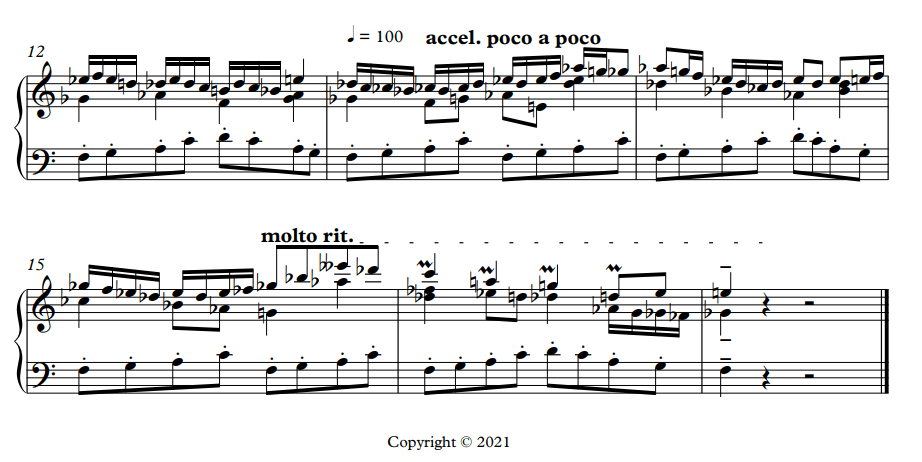

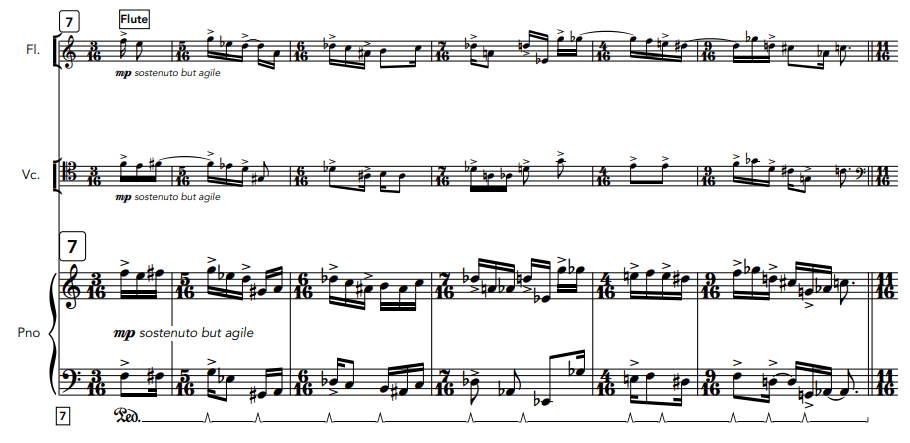

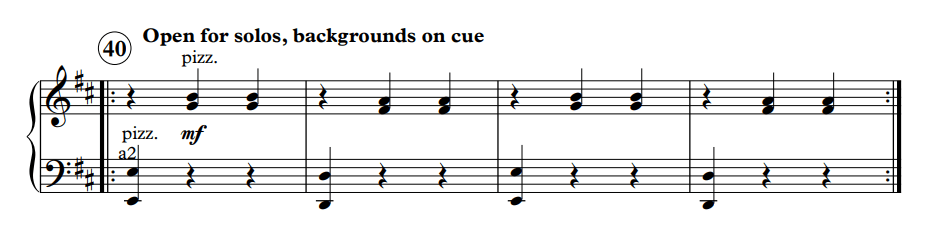

Underneath the soloist is a simple four-bar vamp over two chords: E minor, D major, E minor, D major. This repeats ad lib. to accommodate as many soloists as needed. Non-soloists play the vamp pizzicato, so the soloist can be clearly heard.

Supplemental Materials

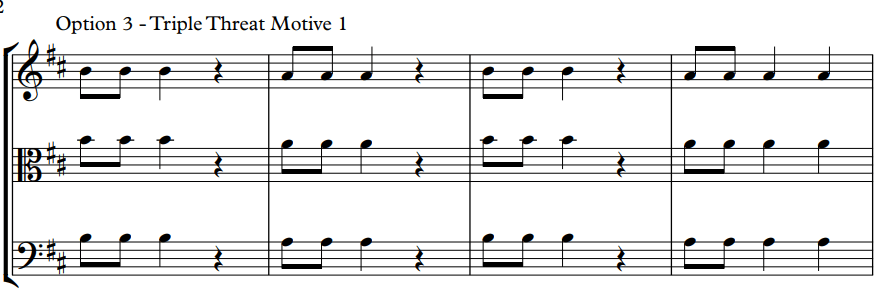

I want this piece to be adaptable to as many situations as possible. Some groups rehearse once a week, or twice a week in block schedule, or every day. As such, I am putting together supplemental materials for the educator to allow some flexibility. Students can improvise the solo, compose their own solo, or use the pre-composed solos. The pre-composed solos are four measures long, and can be combined to however long you want each soloist to improvise – I suggest either 4 or 8 bars each. The solo section can include every performer (which I would prefer!), only some performers, or be skipped (which I do not prefer!).

Suggestions for Educators

I have some suggestions for educators approaching teaching composition and improvisation.

First, give your students limitations to guide and focus their composing or improvising. A blank sheet of paper is overwhelming. In this case, stick to just the notes of D major. Consider improvising/writing for just one string. String crossings can be awkward.

Use rhythmic and melodic motives from the work. Encourage your students to use rests, but sparingly.

Develop a simple motive – for example, in sequence, or inversion.

Combine two or more of these options.

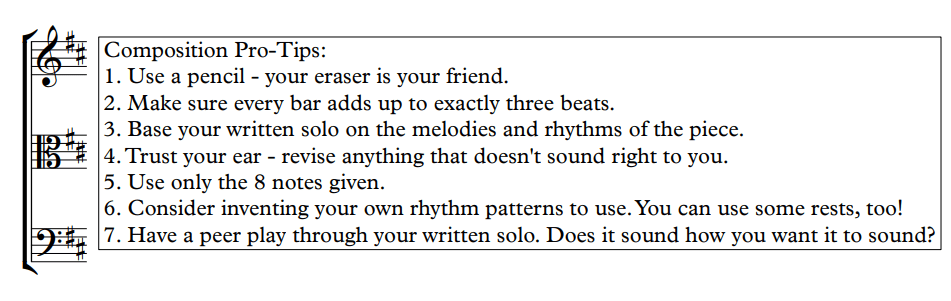

Or, have your students compose their own from these principles. The included supplementary material has 8 blank bars the students can use to write down ideas, with the following instructions (or, perhaps, guidelines) included: